Introduction

Few weeks ago I had the opportunity to attend the SANS course SEC488: Cloud Security Essentials in Paris. Within this course, Identity and Access Management was also a big topic where we covered how Identity and Access Management is covered within the different cloud providers (AWS, Azure or Google Cloud Platform). One topic that we had a deeper look into it was how the whole authentication between an cloud hosted server (e.g. Windows or Linux) and the identity provider looks like. Or in Microsoft Azure terms: How a server hosted in Microsoft Azure authenticate with an Managed Identity against the Identity provider Microsoft Entra ID. To answer this question, the Azure Instance Metadate Service plays an important role in this.

As I’m mainly focused on Microsoft Azure as a cloud platform and the whole Microsoft Security Stack (Microsoft Defender XRD, Microsoft Sentinel), the goal of this blog post is to demonstrate my journey & learnings on how the Azure Instance Metadata service can be abused by an attacker and how we can detect such activities within Microsoft Defender XDR / Microsoft Sentinel.

I will no more describe what the Instance Metadate Service is and how it works in general as there is already a very good blog posts about this from the SANS course Author Ryan Nicholson. I definitely recommend to read this blog post first: Cloud Instance Metadata Services (IMDS) | SANS Institute | Ryan Nicholson.

Attacker perspective: Azure Instance Metadata Service

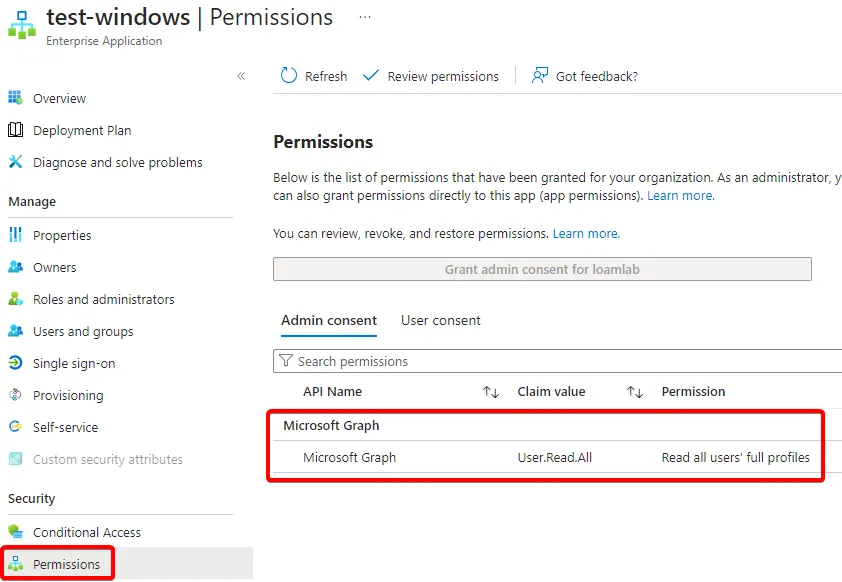

To demonstrate the attackers view I’ve deployed and Windows Server 2022 with an enabled System-Assigned Managed Identity. Additionally for this use cases I assigned the managed Identity the Microsoft Graph permissions User.Read.All. With this permissions the server can read the full set of profile properties, reports, and managers of other users within the organization.

The Azure Instance Metadata Service is, as the name suggests, Microsoft’s solution for instance metadata service. Through this Azure Metadata Service, the cloud-hosted server can receive various information such as SKU, storage, network configurations, upcoming maintenance events and also authentication information.

Retrieve the Bearer Token

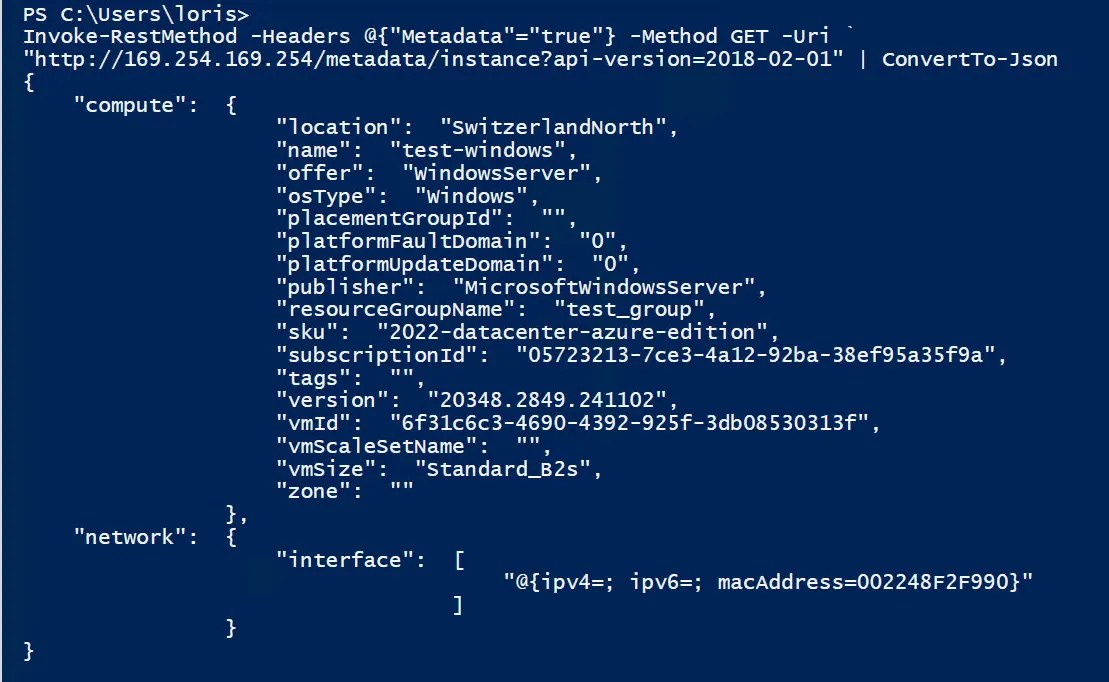

As the Azure Instance Metadata Service runs locally on each machine hosted in the cloud, it’s possible to send an HTTP GET command to the following URL http://169.254.169.254/metadata/instance?api-version=2018-02-01 with the header Metadata=true.

Invoke-RestMethod -Headers @{"Metadata"="true"} -Method GET -Uri `

"http://169.254.169.254/metadata/instance?api-version=2018-02-01"`

| ConvertTo-Json

As you can see, we can now see all the information about the deployed server, which can be quite useful for some use cases. So far, so good.

If you then have ever wondered how the managed identity authentication works on a cloud-hosted server, the Azure Instance Metadata Service plays an important role. When the virtual machine wants to connect to Entra ID (to list all Entra users in our use case), the server/service sends an HTTP GET command to the Azure instance metadata service and requests the required token. This token is provided by the Microsoft Entra ID and the cloud provider Microsoft Azure provides the token to the machine via this service.

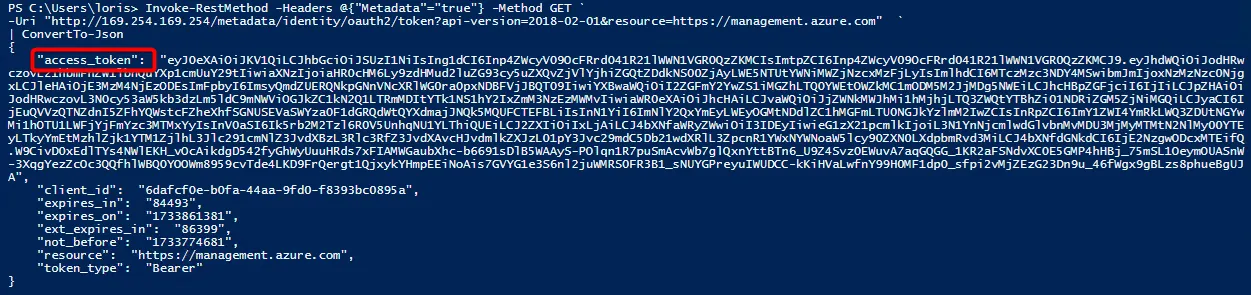

The interesting part is that not only services can access this URL to retrieve tokens, it’s also possible to manually send an HTTP GET command to the local service. To do this, we need to call http://169.254.169.254/metadata/identity/oauth2/token. With the following part of the URL resource=https://graph.microsoft.com we define for which resource we want to get the Bearer Token.

Invoke-RestMethod -Headers @{"Metadata"="true"} -Method GET `

-Uri "http://169.254.169.254/metadata/identity/oauth2/token?api-version=2018-02-01&resource=https://graph.microsoft.com" `

| ConvertTo-Json

As a result, we get the access_token in clear text. The token is called Bearer Token and always starts with ey…which contains all the information about the authorization granted by Entra ID.

Don’t worry, the bearer token has a lifetime of 60 minutes. That’s why I didn’t blur the text in this blog post. Because it has already expired. 😉

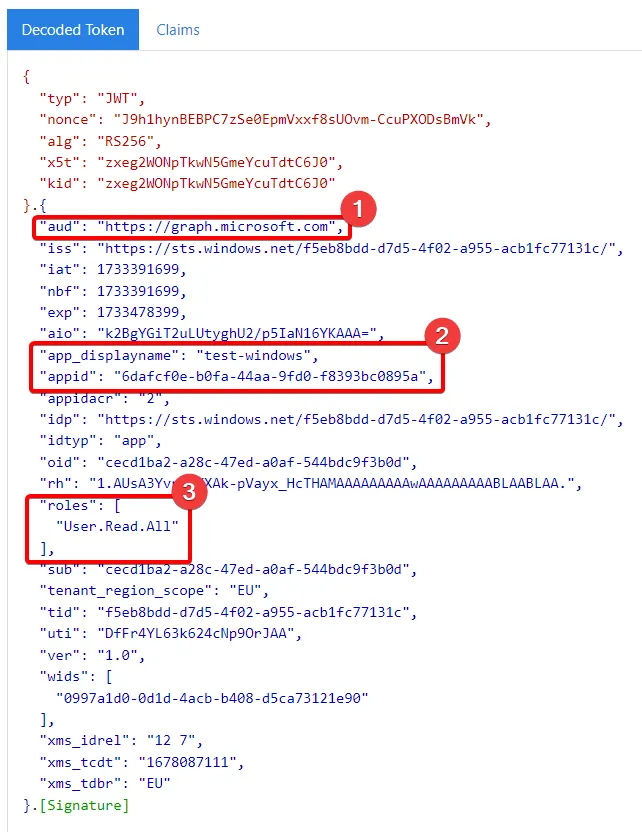

Because the bearer token is difficult to read, and to get more insight into what’s inside the token, it’s possible to decode the bearer token using jwt.ms.

Do not ever enter a production bearer token into a converter, because if the provider of that decoder stores the token, they can also authenticate with that token.

Now we see that the Bearer token was issued for graph.microsoft.com (1), for the Server test-windows and the correlating app id of the managed identity (2) and also the assigned roles User.Read.All (3) which were assigned to the Managed Identity before. So with this token we have the same permissions as the test-windows server also has and we can authenticate to Entra ID as the test-windows server.

Use the Bearer Token as an Attacker

Now that we have the Bearer token, we can use that token to authenticate to Entra ID from an other machine. The reason for this could be that the attacker’s machine is not onboarded to an EDR solution, and an attacker can run various tools that would be otherwise detected by the EDR solution.

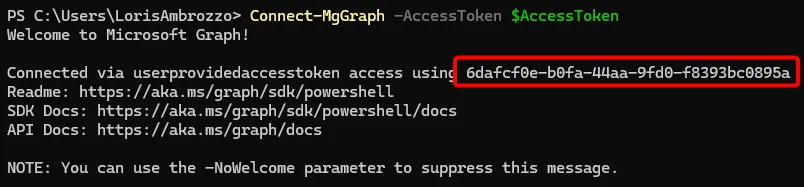

Fortunately, there is an option to use the Microsoft Graph Powershell to authenticate to the Microsoft Graph using an Access Token. I’ve stored the access token from the screenshot above in the $AccessToken variable.

After we authenticated with the Bearer Token, we see that we are now connected to Microsoft Graph with the App ID: 6dafcf0e-b0fa-44aa-9fd0-f8393bc0895a. The App ID is the Managed Identity of the Windows Server.

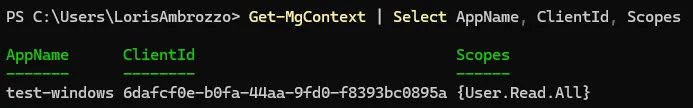

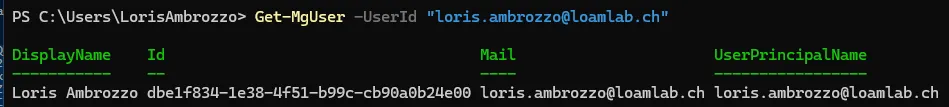

If we take a closer look at the graph context, we see that we are now connected as the Windows Server test-windows with the assigned scope User.Read.All which was previously assigned to the Managed Identity.

And now to complete the whole Attack Story we can now use the Permission User.Read.All to read a specific user in Entra ID.

Of course, with a lot more privileges, the attacker could do a lot more bad things than just read some users. This was just to demonstrate the attacker’s point of view, but it shows again how important least privilege can be in reducing the attacker’s ability to do bad things in your organisation.

Defender perspective: Azure Instance Metadata Service

Moving from bad to good, as I mentioned earlier, I will be using the full Microsoft Defender XDR stack / Microsoft Sentinel to analyse / detect access to the metadata service of the Azure instance.

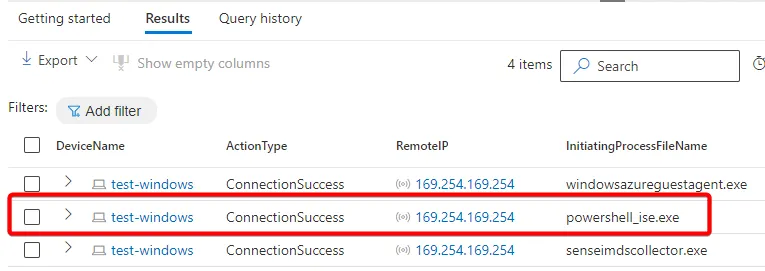

As the server is onboarded to Defender for Endpoint, we can now check the DeviceNetworkEvents table within the Microsoft Defender XDR and filter for any traffic that has the remote IP of the metadata service 169.254.169.254.

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where TimeGenerated > ago(1d)

| where RemoteIP == "169.254.169.254"

| where DeviceName == "test-windows"

| project DeviceName, ActionType, RemoteIP, InitiatingProcessFileName

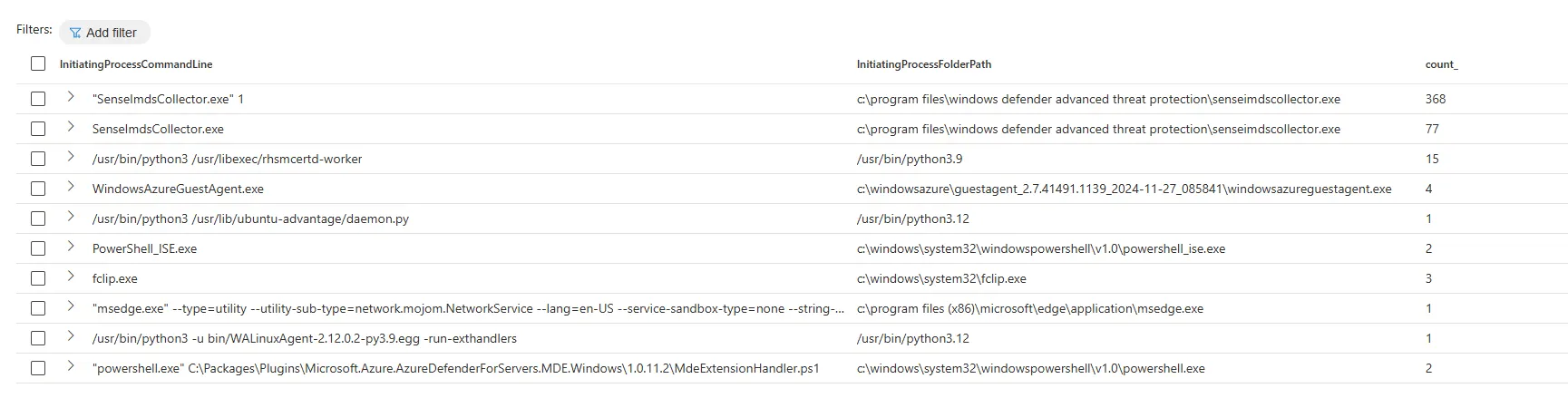

As a result we can see that the request I made earlier from the PowerShell ISE is being logged. We also see other process filenames, but let’s ignore them for now. The good thing is that access to the Metadate service of the Azure instance is logged.

Now I was interested to see if it was possible to detect the “abnormal” traffic to the metadata service, and as we saw in the screenshot above, a lot of other services connect to the service as well. So the first goal was to establish a baseline with an understanding of what is the normal “behaviour” and which services are legit to connect to the service and collect some information. To do this, I made a summary of all my test devices in my lab to see what services were connecting to the service.

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where TimeGenerated > ago(90d)

| where RemoteIP == "169.254.169.254"

| summarize count() by InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessFolderPath

And I was surprised at how many services are connected to this service. Obviously most of them are Microsoft services and legit, but there are a lot of different services.

It is important to note that these services may only collect system status or other information, and not all of them collect bearer tokens. However, if there is suddenly an unknown application that connects to the metadata service, it might be worth investigating it further to find out what unknown software is running on the system.

In order to detect abnormal activity, my goal was to eliminate such large lists of legit services in the results pane of the query. To do this, I ran several tests on different servers and operating systems to get a feel for which services were legit Microsoft services.

From this I’ve developed the following KQL query. In this query I’ve defined the following allowed services that will be excluded from the results.

- senseimdscollector.exe: Service part of Microsoft Defender for Endpoint.

- WindowsAzureGuestAgent.exe: Microsoft Azure Windows VM Agent

- attestationclient.exe: Microsoft Azure Attestation service

- gc_worker: Azure Policy Guest Configuration Service, Linux

- gc_linux_service: Azure Connected Machine agent

- WaAppAgent.exe: Azure VM Agent is a virtual machine (VM) agent

- MdeExtensionHandler.ps1: Microsoft Defender for Endpoint Extension Service

let ExcludedProcesses = dynamic([

"senseimdscollector.exe",

"WindowsAzureGuestAgent.exe",

"attestationclient.exe",

"gc_worker",

"gc_linux_service"

]);

let ExcludedCommandLines = dynamic([

"WaAppAgent.exe"

]);

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where TimeGenerated > ago(90d)

| where ActionType == "ConnectionSuccess"

| where RemoteIP == "169.254.169.254"

| where InitiatingProcessFileName !in~(ExcludedProcesses) and InitiatingProcessCommandLine !in~ (ExcludedCommandLines)

and not(

InitiatingProcessCommandLine matches regex

@"C:\\Packages\\Plugins\\Microsoft\.Azure\.AzureDefenderForServers\.MDE\.Windows\\\d+\.\d+\.\d+\.\d+\\MdeExtensionHandler\.ps1"

)

| summarize count()

by

InitiatingProcessFileName,

InitiatingProcessCommandLine,

InitiatingProcessFolderPath

| sort by count_ desc

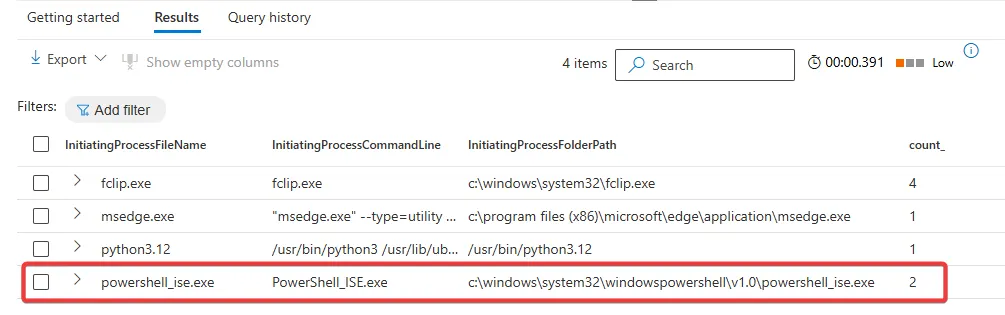

Now, when we run the KQL query again in Microsoft Defender XDR, we only see the services that are not excluded and also our test access from Powershell_ISE and some other services that access the Metadate service, such as msedge.exe, which I also tried to use to retrieve some data from the Metadata service. So the list is much smaller then before. This smaller list of results makes it now easier to analyse the not known services which are connecting to the Azure instance metadate service.

Important note to my query: During my field tests, I defined the above exclusion for relatively standard deployed servers within Microsoft Azure. What I have found is that it really depends on what additional Microsoft Azure services you are using in your organisation. So the above KQL query is a good starting point for discovery, but you will definitely need to adapt it to the services you have active in your environment, and then create your own baselines for the excluded services. For example, I’ve also seen other services accessing the Azure instance metadata service like IaaSWorkloadCoordinatorService.exe (Azure SQL Backup Service), NetworkWatcherAgent.exe (Microsoft Network Watcher Service), sqlceip.exe (MS SQL Server) which I haven’t added to the default query because not everyone uses these services, but you can add them manually to my query.

In the end, I’ve noticed for myself that it’s very tricky to write an “out-of-the-box” detection rule, because it’s very dependent on the services that are running, and also new Microsoft services maybe will be added and the detection gets too many hits. However, the query provides a very good overview of which services are actively trying to get information from the metadata service in your organisation.

Additional: It occurred to me while writing this blog post that it might also be possible to detect misused bearer tokens via the Azure Instance Metadata Service using the MicrosoftGraphActivityLogs. But maybe that’s something for a future blog post.😉

Conclusion

In this blog post I wanted to share my experiences & learnings with the Azure Instance Metadata Service which was for me very interesting to see how the whole authentication works and how easy it is to get the access token from a server. Of course you still need access to the server, but after that it’s quite easy and it showed once again how important least privilege is also for all Azure resources and not just the user / admin accounts.

As I mentioned above, the discovery KQL query is a good starting point, but it definitely needs to be adapted to the services you have active in your environment. Last but not least, it was fascinating for me to see how the different services interact with the metadata service.

If you have any input, feedback or additional information that you think would be of interest to me and the community, please feel free to add a comment below this blog post.

See you next time, Loris 👋

Used Sources in this blog post

- Azure Instance Metadata Service for virtual machines — Azure Virtual Machines | Microsoft Learn

- Cloud Instance Metadata Services (IMDS) | SANS Institute | Ryan Nicholson

- Azure Instance MetaData Service — Find out Azure information from within guest OS

- Access tokens in the Microsoft identity platform — Microsoft identity platform | Microsoft Learn